Fruit of the Same Tree

St. Valentine’s Day and Ash Wednesday, believe it or not, are fruit of the same tree. Granted, that’s not apparent to everybody. The last time the two feasts shared the same space on the calendar a priest well known on theh internet posted the following: “This year nothing says happy Valentine’s Day like taking your date to get your ashes in church and reminding each other that one day you are both going to die.”

Romantic, no? Fr. was making a knowing nod to the fact that some people don’t see the convergence. And there does, on the surface, appear to be a conflict between bright pink hearts on the one hand, and ashes against a deep purple backdrop on the other. In my own diocese the bishop has already pre-emptively announced that he will not be granting any dispensations from the mortifications of Ash Wednesday in deference to the yearly love fest.

“Remember, Man . . .”

But is there a conflict, really? The coincidence of these two days should not be a problem for us if we hold to the Faith As Handed Down To Us. The “Valentine’s Day” promoted by retailers and other secular sources, after all, started out as the Feast of St. Valentine, who was a 3rd century Christian martyr. Not only do both observances spring from the same Christian tradition, they actually complement each other in a way that is particularly relevant to our current situation.

Let’s start with Ash Wednesday, which marks the beginning of the great penitential season of Lent. Its name comes, naturally, from the imposition of ashes on the forehead, along with the admonition “remember, man, that you are dust, and unto dust you shall return.”

The Fall

This reminder of our dusty origin is taken from Genesis 3:19, at which point the Lord is expelling Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden. This after our first parents have eaten, at Satan’ behest, from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. In our Ash Wednesday observances we have a concrete reminder that, through original sin and its effects, The Fall is still an operative reality in our lives.

The Fall destroyed the close relationship between humanity and God, which we see when Adam and Eve hide from their Creator in the Garden. It likewise creates division in the one-flesh union between the two of them. Consequently, they now feel the need to hide their bodies from each other with clothes, since each now feels the greedy power of lust as a consequence of original sin, and perceives it in the other.

Carnal Desire

Concupiscence is the theological term for the attraction to sin that is one of the consequences of Original Sin. Lust is by no means its only manifestation, but it has always been one of its most prominent features, and one which heavily overshadows our age. In fact, lust lies at the heart of virtually every major point on which the secular world, and the culture of dissent within the Church that is secularism’s close ally, takes issue with traditional Catholic moral teaching. Lust permeates our popular culture.

It is not surprising, then, that as the Feast of St. Valentine has been gradually transformed into the bacchanalia known as Valentine’s Day (or sometimes simply “V” Day) it has become, more or less, a straightforward celebration of carnal desire.

Husbands, love your wives, as Christ loved the Church and gave himself up for her, that he might sanctify her . . . (Eph 5:25-26)

Carnality, however, was not the program of the real St. Valentine (as I detail in a previous post, “St. Valentine, Patron of Agape”). The historic Valentine was put to death by the Romans, according to some accounts, for consecrating Christian marriages. Now, the Romans married as much as anyone else, there was no crime in presiding over marriages per se. The crime was in the consecrating of Christian marriages. St. Valentine was a champion of marriage as raised to a sacrament by Jesus Christ. He willingly sacrificed his own life for this understanding of marriage.

The Convergence

It is here that we begin to see the convergence between the supposedly divergent observations of Ash Wednesday and St. Valentine’s Day. We see how they can be the fruit of the same tree. On Ash Wednesday we are called to repent, to turn aside from concupiscence in all its forms and surrender ourselves to Christ. The Christian marriage for which St. Valentine gave his life likewise calls us to turn aside from selfish lust, and, in imitation of Jesus, sacrifice ourselves for our spouse. As St. Paul says:

. . . walk in love, as Christ loved us and gave himself up for us, a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God. (Eph 5:2-3)

Later he adds:

Husbands, love your wives, as Christ loved the Church and gave himself up for her, that he might sanctify her . . . (Eph 5:25-26)

Christian love consists in sacrificing oneself for the good of others, and a Christian expresses sexual love precisely by sacrificing oneself for one’s wife or husband within the sacramental covenant of marriage. Most often this also includes sacrificing one’s own wants, desires, and comfort for the good of the children that result from the union.

Sanctify Each Other

Let’s return for a moment to that first human marriage in the Garden of Eden. We saw how concupiscence is an impediment to love: love between the spouses, and love between the spouses and God. Turning away from sin (i.e., repenting) is the only thing that makes true love possible. If we want true love, we must indeed “Repent and believe the Gospel”.

Love and Repentance, fruit of the same tree. This Ash Wednesday my date, as the internet priest put it, will be my lovely bride. That is, my sweetheart of more years than I care to enumerate (along with at least one of our fair offspring). We’re going to church and getting our ashes . . . that we might sanctify each other.

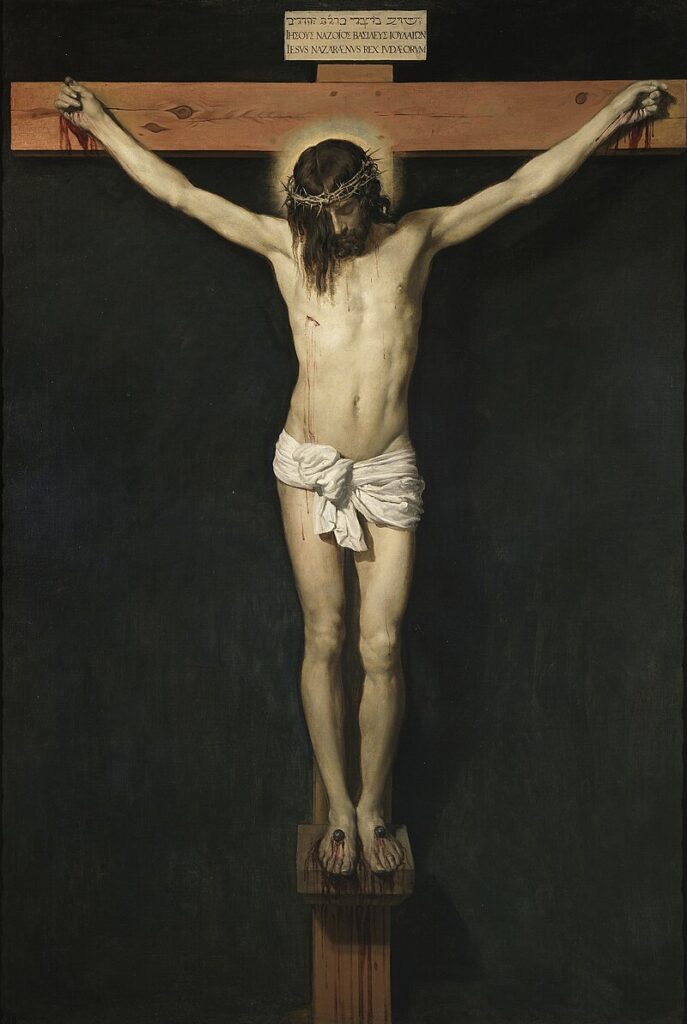

Featured image top of page: Ash Wednesday, by Julian Falat, 1877